- Home

- McDowell, Michael

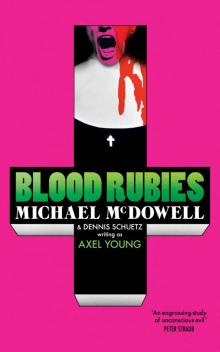

Blood Rubies

Blood Rubies Read online

CONTENTS

Prologue

PART I: Katherine

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

PART II: Andrea

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

PART III: The Hammers of Heaven

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

Epilogue

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Also Available by Michael McDowell

The Amulet

Cold Moon Over Babylon

Gilded Needles

The Elementals

Katie

Toplin

Wicked Stepmother (with Dennis Schuetz)

BLOOD RUBIES

Michael McDowell

& Dennis Schuetz

(writing as Axel Young)

VALANCOURT BOOKS

Dedication: For Alice and Bernard Schuetz

Originally published by Avon Books in 1982

First Valancourt Books edition 2016

Copyright © 1982 by Michael McDowell and Dennis Schuetz

Published by Valancourt Books, Richmond, Virginia

http://www.valancourtbooks.com

All rights reserved. In accordance with the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, the copying, scanning, uploading, and/or electronic sharing of any part of this book without the permission of the publisher constitutes unlawful piracy and theft of the author’s intellectual property. If you would like to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), prior written permission must be obtained by contacting the publisher.

Cover by Henry Petrides

Now that you are sweetly dead to the world,

and the world dead in you,

that is only a part of the holocaust.

Saint Francis DeSales

Prologue

Leaden clouds driven in from the west hastened the end of a frigid winter day. All of Boston was bathed in chill blue twilight. The vast reflective surfaces of the harbor and the Charles River subsided from dull silver into blackness. By nine o’clock the low clouds domed the city, and the predicted snowstorm seemed inevitable. Still, in the final hour of the day, the year, and the decade, anticipation of midnight, 1 January 1960, far outweighed Boston’s concern over the possibility of a snowstorm. On Beacon Hill, braceleted hostesses discreetly shuttered their windows against the harsh glare of the lightning; in the barrooms of the West End and along the waterfront, the jukeboxes and the television sets were turned up to cover the noise of the thunder.

The temperature dropped steadily as a chill wind streamed in from the Atlantic.

On the corner of Salem and Parmenter Streets in Boston’s North End, the dusty windows of a four-story tenement rattled with each explosion of thunder. The building, constructed in the eighteen fifties for a prominent judge and his two motherless children, was now home to some forty people, most of them of Italian extraction.

In several of the windows hung poignant attempts at holiday cheer. Suspended lopsidedly by the neck in one cloudy window was a small fat Santa Claus, illuminated by a red light shining garishly through his broken plastic face. Two floors below, the Virgin Mary perched precariously on a narrow sill, one raised hand poking through a jagged hole in a windowpane, as though signalling for assistance from someone passing below, along Salem Street.

Within, the glum hallways and staircase were laid over with the texture of noise from every apartment, every room. Even those flats whose occupants were out contributed the sounds of shuddering, malfunctioning refrigerators, hissing radiators, mewling and yapping pets, even radios, left on to discourage any burglar stupid enough to come to such a place as this.

Heated voices of two men and a woman on the fourth floor, all shouting in coarse Italian, rose over the noise of a dozen television sets, all tuned to Guy Lombardo’s orchestra playing “White Christmas.” The caterwauling of small children sputtered here and there on the lower floors.

Outside, hail fell suddenly from the night sky, smashing against the streets and buildings like machine-gun fire. Lightning, in blinding, flashing waves, lighted up the pellets of ice as they fell. A flock of bedraggled pigeons that made their home on the roof of the tenement suddenly flew down and took refuge in the leafless forsythia that lined the building on Parmenter Street.

The scantily furnished bedroom of the third-floor corner apartment was illumined only by a chipped Kewpie-doll lamp on a table next to the door. Its pale light fell softly over the face of the woman who writhed beneath the stiff, soiled sheets of the narrow bed. She was young, no more than nineteen.

Mary Lodesco’s head was thrown so far back on the pillow that her shoulders were arched entirely off the bed. Her teeth were clenched and bared, and her body twisted as another spasm of pain shot through her. Her knuckles whitened as she grasped the rungs of the iron bedstead, and the black paint dropped in flecks over her forehead and the top of the sheet.

Thick with salt and mucus, tears flowed from her tight-shut eyes. Discolored saliva glistened at the corners of her mouth. The spasm passed and the woman dropped heavily onto the mattress, breathing laboriously. Behind her head, Mary Lodesco’s hands slid to the bottom of the rungs. Her head lolled to one side, and her blond hair fell in damp tangles across the pillow.

Flashes of chain lightning seared the room to a brilliant white, and the thunder that followed immediately shook the walls and rattled all the windows. The woman in the bed cried out. Her green eyes were filled with terror, and her fingers pressed hard against her enormously bulging belly.

In the next half hour the shower of hail slackened, then regained its strength. The tiny pellets of ice that smashed on stone and concrete melted, only to be frozen together again. Sheets of perilously slick ice formed over streets and sidewalks.

Theresa Lodesco stood with her knees pressed against the cold frame of the iron bed as she gazed at her daughter Mary. A floor lamp, with its shade removed, had been brought in from the adjoining bed-sitting room occupied by the old woman.

Nestled in Mary’s arms were two baby girls, thin and pink and unmoving beneath their linen wrappings. The mother, holding them protectively in her quaking arms, looked wearily from one child to the other. Ice pelted the two windows of the room. The radiator hissed weakly and sent up steam that obscured the view of Parmenter Street.

Mary Lodesco inclined her head to stare up at her mother.

“This one,” Theresa was saying, pointing to the infant in its mother’s right arm, “was born in nineteen fifty-nine. Then the bells chimed, and the other one came. She was born in nineteen sixty. And those two can thank God for the rest of their lives that the midwife came on a night like this.”

With apparent effort, Mary Lodesco whispered, “The rings . . .”

Confusion creased Theresa’s face. Mary Lodesco flopped one hand weakly beside her head and touched a minute

gold earring set with a sliver of ruby. An identical jeweled setting pierced her other ear. “The babies,” she whispered. “Pierce them . . .” she gasped finally, as if with the last of her strength.

“They’re too young!” exclaimed her mother.

“Pierce them! One for each.”

Theresa turned her face away. “They’re too young. They . . .” She sighed and settled her bulk onto the edge of the bed. She touched one of the little girls with the back of her hand. “My mother gave them to me, and her mother gave them to her, and so on back before anyone could remember. The oldest daughter gets them, but . . .” She waved her hand over the babies: “. . . you have two!”

“It’s all I have to give them!” rasped Mary Lodesco. “Do it!”

Theresa sighed. In a few minutes she returned from the other room with a cup of ice, alcohol, cotton, and a large sewing needle.

Each child lay for a few seconds across her grandmother’s wide lap. A ruby earring—all that their mother had to give them in this life—was secured in the left earlobe of one of the infants, and in the right earlobe of the other. “Not good,” Theresa muttered darkly. “Not good to separate the rubies. Bad luck—bad luck will follow until the rubies are together again . . .”

When she had returned the second infant to the cradle of its mother’s arm, Theresa Florenza went to the window over Salem Street and sighed. “The storm is nearly gone.” She glanced once more at the new mother: “You’re so thin—no flesh on you. Hardly enough to give to one baby—and now you have two. How will we take care of them?” Theresa Lodesco muttered a short prayer, twice over, for the souls of the two infants whose lives she did not believe would be of more than a week’s duration. Without another word, she snapped out the light and returned to her own room, closing the door behind her.

In the hour after midnight, many of the inhabitants of the tenement at the corner of Salem and Parmenter had taken themselves to bed. Mary Lodesco and her twin infant girls slept; in other apartments the children who had, only with difficulty, remained up until the chiming of the New Year’s bells now slumbered soundly. And in the room at the very back of the first floor, an old man fell into the dead sleep of the confirmed alcoholic. The cigarette he had lighted only a moment before, the last in the pack, slowly dropped from his fingers. The hot orange tip of the cigarette rapidly burned down and ignited the mattress ticking. Tiny serrated flames crept across the edge of the mattress toward the cuffs of his grease-stained trousers.

Mary Lodesco snapped her head up, eyes wide, her mind alert but without memory. She stared about the darkened room, and then gasped as a tiny claw brushed against her breast. Then she felt the two infants nestle against her at the same time, in just the same manner, and the remembrance of the terrible labor and delivery flooded back. She cut it off with a smile directed at her two little girls. Both infants began to cry at once. With heavy-lidded eyes, their mother regarded their tiny, insistent hands.

Slowly the sounds of running feet and garbled shouts in the hallways brought her to full, if perplexed consciousness. She struggled to sit up. The room was as uncomfortably hot now as before it had been cold. Then, at the same time she felt the discomfort in her eyes and her throat, she saw the thin veil of smoke wafting across the blue light from the two windows.

The infants shrieked, and their cries blended with the approaching sirens outside. From the street there was a babble of moanings and shouts of distress. Audible beneath it all were pinpoint sounds of shattering, tinkling glass, and a dull, low-volumed roar that Mary Lodesco could not identify.

She eased out of the bed, sliding the babies close together into the center of the sagging mattress. When she tried to stand on her feet, she doubled over with the pain that shot up from her groin. She grasped the foot of the bed for support, crying out until the pain had subsided. She stood erect, breathing hard, and stumbled to the front window. Salem Street was amass with people, dark and colorless, all standing with black mouths agape.

A bright arrow of flame, fiercely colorful amid the black-and-gray scene, shot out of the window just below her, and Mary Lodesco gasped in terror. She unlatched her window and tried to slide the frame up, but ice had frozen into the wooden seams and held it fast.

In the street, firemen from two trucks dragged out the hoses and rapidly fixed them to hydrants down the way. An ambulance appeared, coming the wrong way up Parmenter Street, the drivers bringing the vehicle right up against the fire engine that blocked the intersection. Two attendants jumped out with stretchers.

All the inhabitants of Salem Street leaned out their windows. Those who had no view came out into the cold, watching, horrified, as an old woman trapped on the third floor of the building flitted past orange windows, her hair turned to matchsticks of flame.

On Parmenter Street, the views of the burning building were obscured by smoke. The only spectator here was a young woman returning home to her ill husband after a long formal dinner at Polcari’s restaurant. She wore a black wool coat over a full-length white evening gown. A white woolen shawl was draped over the woman’s shoulders, and she held one corner of it to her mouth against the cold. Her eyes darted up the building and stopped at the third-floor corner window. She drew in her breath sharply as she watched a woman trying to break open the window with one hand, holding in the other a small white bundle.

Mary Lodesco drew back from the window over Parmenter Street. She hit at the frozen wooden frame as she held one of her daughters tight against her breast. Tears of fear and frustration streamed down her soiled face. The room was filled with smoke, and flames ate steadily at the bottom of the door.

Mary lunged, her arm straight out, the hand splayed open. The glass smashed, shearing open her hand in half a dozen deep cuts. She grabbed at the sticks in the frame and, not minding the shards of glass still stuck there, ripped out the wood. She ran back to the bed and slung the single pillow out of its sweat-stained case. She dropped the baby into the cotton sack, swung it round a couple of times to close the infant in, and then carefully pushed the case through the large hole that she had made in the window over dark Parmenter Street.

“Wait for the net!” cried the woman in the black coat and the white evening gown. For a brief, intense, unthinking moment, Mary Lodesco locked eyes with the woman below, who, as if mesmerized, had moved directly below the window.

Mary Lodesco opened her bloody hand, and the pillowcase dropped three stories.

At the last instant the woman below threw out her arms and caught it. She looked up again in surprise, but Mary Lodesco had already retreated from the window. She slipped on a patch of ice and fell to her knees, ripping open her white gown, but the bundle was still in her arms.

The bloody top of the pillowcase slowly unwound itself and a little bloody hand shot out into the cold night.

Mary Lodesco, afraid to know whether the woman had caught the baby or not, grabbed up her second child. She was possessed by a single thought—that at least one of her daughters should survive. She yanked the blanket off the bed and wrapped it carefully about the silent form. She could not see for the thickness of the smoke, and could not catch a breath to fill her lungs. She began to cough uncontrollably. Blood poured out of her right hand.

Mary Lodesco collapsed and sprawled heavily on the floor. Flames shot under the door and surged towards her in thin parallel lines along the floorboards. She crawled toward the window over Salem Street, pulling after her the baby, almost smothered in its blanket. Her hope for the child provided her strength. Pressing the infant to her breast, she struggled to her feet. But with that motion she lost all and fell with full force against the window frame. The frame splintered and Mary Lodesco died, her abdomen pierced by a sharp peak of shattered glass.

The crowd on Salem Street uttered a great cry as the woman’s body thrust through the third-floor window. The falling shards, caught in the great

spray of one of the hoses, were smashed against the side of the building. The blanket in the dead woman’s arm was tossed free, and the firemen below instinctively jerked the net to catch the falling object. The blanketed bundle hit the rim of the net and bounced into a large puddle of icy water in the street.

In a black recessed doorway on Parmenter Street, Vittoria LoPonti gazed at the naked infant whose face bore the imprint of a bloody hand. The sliver of ruby in its ear dully reflected the orange fire in the tenement house. She carefully wrapped the child in her white shawl, and kicked the empty pillowcase aside. Holding the child tight to her breast, she hurried along Parmenter Street, dodging precariously through the crowd on her high heels, glancing neither at the firemen, nor at the rapt crowds, nor at the moaning victims who were being lifted into the backs of the ambulances.

PART I: Katherine

1

Fourteen persons were thought to have perished in the terrible North End tenement fire of New Year’s Eve, 1959. This number included Mary Lodesco, her mother, Theresa, and one of the pair of infants who had been not an hour old when the blaze broke out. The existence of this child was known at all only through the testimony of the midwife who had attended the double birth.

The baby girl that had bounced out of the firemen’s net into an icy puddle on Salem Street was taken to Massachusetts General Hospital, kept there for seventeen days, and then released to a state adoption agency. Seven months later the baby was adopted by James and Anne Dolan and named Katherine, after Mrs. Dolan’s grandmother.

The puny child was brought home that hot July afternoon in 1960 to the second-floor apartment of a triple-decker house on Medford Street in Somerville, where the Dolans had lived since their marriage seven years before. Below the couple’s two-bedroom flat was another just like it, and a third one stood just above. On their block were five identical buildings to the left and four more identical buildings to the right. Across the street was another block with ten triple-deckers, and eleven had been squeezed onto the block behind. And in the winter, when the dying maples and the vigorous oaks had lost their foliage, Anne Dolan had a view of two dozen more blocks of triple-deckers; they extended in every direction from the house on Medford Street.

Blood Rubies

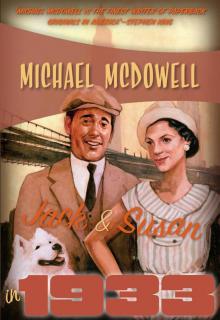

Blood Rubies Jack and Susan in 1933

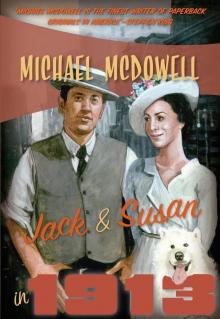

Jack and Susan in 1933 Jack and Susan in 1913

Jack and Susan in 1913 Cold moon over Babylon

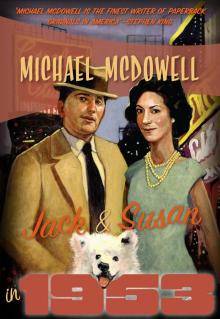

Cold moon over Babylon Jack and Susan in 1953

Jack and Susan in 1953